|

A Brief Historic Overview: Introduction

In order to carry forward the sacred musical tradition central to oricha worship in Cuba, its bearers had to endure unimaginable violence and persecution; first surviving the middle passage as enslaved Africans on their way to Cuba, and then the inhuman conditions on plantations where they and their descendants were forced to work as slaves. Throughout the history of the religious practice of Regla de Ocha in Cuba and the United States, practitioners have had to fight to gain respect for their beliefs and spiritual practices. Although we have now arrived at a place where people are legally free to practice their religion and its music without fear of persecution, both in Cuba and the diaspora the majority of professional ritual oricha musicians are people of colour and continue to be confronted with racial discrimination. Echoing the story of their African ancestors, Cuban ritual musicians who arrived in Miami, whilst enduring the trauma of relocation, brought their sacred sound to the shores of the United States. They arrived not only with a responsibility to their religious community, but also to their descendants who fought to protect and maintain the tradition before them The legacy of this music is not only that it communicates with the Gods, or that it can now be heard resonating throughout the world, but of its survival in the face of adversity. This site pays homage to one aspect of this journey – ritual oricha music in Miami. [1] |

Vertical Divider

Una Breve Reseña Histórica: Introducción

Con el fin de llevar adelante la tradición musical central sagrada para el culto oricha en Cuba, sus portadores tuvieron que soportar la violencia inimaginable y persecución; primero sobrevivir a la travesía del Atlántico como esclavos africanos que se dirigían a Cuba, y luego las condiciones inhumanas en las plantaciones donde ellos y sus descendientes fueron obligados a trabajar como esclavos. A lo largo de la historia de la práctica religiosa de la Regla de Ocha en Cuba y los Estados Unidos, los médicos tuvieron que luchar para ganar el respeto de sus creencias y prácticas espirituales. Aunque ahora hemos alcanzado un lugar donde las personas son legalmente libres de practicar su religión y su música sin temor a la persecución, tanto en Cuba como la diáspora la mayoría de los músicos profesionales de ORICHA ritual son personas de color y continúan haciendo frente a la discriminación racial . Haciendo eco de la historia de sus antepasados africanos, músicos rituales cubanos que llegaron a Miami, mientras que soportar el trauma de la reubicación, llevaron su sonido sagrado a las costas de los Estados Unidos. Llegaron no sólo con la responsabilidad de su comunidad religiosa, pero también a sus decendientes que luchaban para proteger y mantener la tradición antes de ellos El patrimonio de esta música no es sólo que se comunica con los dioses, o que ahora se puede oír resonar en todo el mundo, sino de su supervivencia entre la adversidad. Este sitio es un homenaje a uno de los aspectos de este viaje - oricha música ritual en Miami. [1] |

|

The toqué (rhythm) Áro is played for the oricha Yemaya in the oru seco, a musical sequence played on batá at the beginning of a ceremony saluting each of the main orichas with their specific rhythms. L-R: Daniel Raymat (Itótele), Maquito (Iyá), Daniel Raymat (Okónkolo). (Filmed by Vicky Jassey: 2nd April 2017).

|

Del toque (ritmo) Aro se reproduce durante el oricha Yemaya en el seco oru, una secuencia musical tocado en batá al comienzo de una ceremonia saludando cada uno de los principales orichas con sus ritmos específicos. LR: Daniel Raymat (Itótele), Maquito (Iyá), Daniel Raymat (Okónkolo). (Filmado por Vicky Jassey: 2o de abril de 2017).

Vertical Divider

|

|

First Wave: Ritual oricha music in the United States up until the 1980s

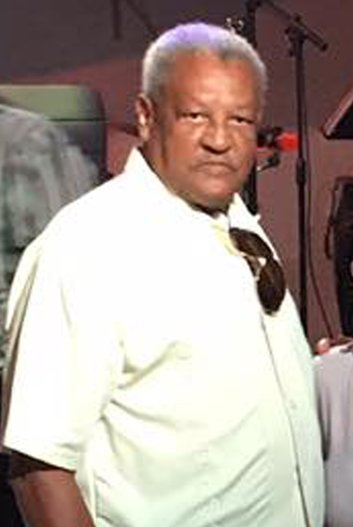

Katherine Dunham is credited in written accounts, as being one of the first to introduce oricha music into secular performance in the United States from the 1940s onwards. She was also responsible for bringing two influential Cuban drummers, Julito Collazo and Francisco Aguabella to the United States in 1952, as well as the first set of aberikulá (non-consecrated batá drums) from Cuba in 1953. The earliest recorded account of batá being played in the United States happened that same year in Las Vegas. [2] 1961 saw the first major public tambor led by Collazo who went on to become a pioneer of ritual oricha music in New York where the practice of Regla de Ocha was flourishing. [3] However, it has been suggested that the level of musical knowledge available at the time was somewhat limited. For example, John Amira, an American ritual drummer, explained that during his time with Collazo, who he met in 1961, he only ever saw him play chachalokefun (a batá rhythm used to play for many orichas) on a double-sided Kenyan drum, which he used as an iyá (principal batá drum); this was played alongside a conga and shekere (beaded gourd). The combination of instruments and the fusing of two styles, batá and güiro, suggests a distinct departure from the protocols of a traditional musical ceremony happening in Cuba at the time. [4] The main problem for the burgeoning religious community in the United States at this time was the absence of Añá, the deity believed to reside in fundamento. To become fully initiated into Regla de Ocha devotees need to be presented to Añá in a religious musical ceremony. As there were no fundamento drums in North America and travel to Cuba was prohibited as part of the political embargo, full initiation of Santeros (religious devotees) was not possible making the demand for fundamento batá ever greater as the community expanded. In the meantime, the religious community in the United States honoured their deities in ceremonies using güiro or aberikulá. In response to this demand, the first presence of Añá in the United States, Dr Willie Ramos explains, came about in Miami when Pipo Peña, a Cuban living in Miami since 1960, consecrated a set of batá drums along with sixteen babalawos in 1975 and it was here that Añá began its story in North America.[5] It is generally considered that as part of the consecration process batá have to be ‘born’ from an existing set of fundamento, therefore, like the first set of batá consecrated in Cuba (circa early 1800s), Pipo’s fundamento were consecrated in somewhat unorthodox circumstances. The drums were first played in Miami before travelling to New York. According to Ramos, Peña, his sons Arturo and Reynaldo, and Collazo became the first consecrated batá drummers on North American soil. Juan Candela, Francisco Aguabella and Onelio Scull were among those early pioneers of ritual oricha music in New York, which at the time was the hub of Regla de Ocha activity. [7] Dr Willie Ramos suggests Juan Candela was probably one of the first batá drummers in Miami with Mario Arango and Onelio Scull being the first to bring consecrated batá from Cuba to the United States. (pers.comm 9th March 2017) Pipo Peña circa 2017

|

Primera Ola: la música oricha ritual en los Estados Unidos hasta la década de 1980

Katherine Dunham se acredita en cuentas por escrito, por ser una de las primeras en introducir la música en el rendimiento oricha secular en los Estados Unidos desde la década de 1940 en adelante. Ella también fue responsable de la unión de dos influyentes tamboristas cubanos, Julito Collazo y Francisco Aguabella llegaron a los Estados Unidos en 1952, así como el primer conjunto de aberikulá (no consagradas tambores batá) de Cuba en 1953. La cuenta registrada más temprana del ser batá jugado en los Estados Unidos pasó ese mismo año en las Vegas. [2] 1961 vio el primer tambor importante público dirigido por Collazo, que se convirtio en un pionero de la música oricha ritual en Nueva York, donde florecía la práctica de la Regla de Ocha. [3] Sin embargo, se ha sugerido que el nivel de conocimientos musicales disponibles en ese momento era algo limitado. Por ejemplo, John Amira, un baterísta ritual estadounidense, explicó que durante su tiempo con Collazo, a quien conoció en 1961, sólo alguna vez lo vio jugar chachalokefun (un ritmo batá solía jugar para muchos orichas) en un tambor de Kenia de doble cara , que utilizó como un iyá (principal tambor batá); esto se jugó junto a una conga y shekere (calabaza con cuentas). La combinación de instrumentos y la fusión de dos estilos, Bata y güiro, sugiere un punto de partida distinto de los protocolos de una ceremonia tradicional musical pasando en Cuba en el momento. [4] El problema principal de la comunidad religiosa creciente en los Estados Unidos en ese momento era la ausencia de Ana, la deidad que se creia que reside en fundamento. Para llegar a ser completamente iniciado en devotos Regla de Ocha necesitan ser presentados a Ana, en una ceremonia religiosa musical. Como no había tambores de fundamento en América del Norte y los viajes a Cuba se prohibieron como parte de embargo político, la iniciación completa de Santeros (devotos religiosos) no fue posible hacer la demanda de batá fundamento cada vez mayor a medida que la comunidad se expandió. Mientras tanto, la comunidad religiosa en los Estados Unidos honor a sus dioses en ceremonias utilizando güiro o aberikulá.En respuesta a esta demanda, la primera presencia de anticuerpos antinucleares en los Estados Unidos, el Dr. Willie Ramos explica, se produjo en Miami cuando Pipo Peña, un residente cubano en Miami desde 1960, consagra un conjunto de tambores batá, junto con dieciséis babalawos en 1975 y fue aquí que Añá comenzó su historia en América del Norte. [5] En general se considera que parte del proceso de consagración batá tiene que ser 'nacido' de un conjunto existente de fundamento, por lo tanto, al igual que el primer juego de batá consagrados en Cuba (circa principios de 1800), fundamento de Pipo se consagró en unas circunstancias un poco ortodoxias. Los tambores fueron jugados por primera vez en Miami antes de viajar a Nueva York. Según Ramos, Peña, sus hijos Arturo y Reynaldo, y Collazo se convirtieron en los primeros tambores batá consagrados en suelo norteamericano. Juan Candela, Francisco Aguabella y Onelio Scull estaban entre los primeros pioneros de la música ritual oricha en Nueva York, que en ese momento era el centro de la actividad Regla de Ocha. [7] El Dr. Willie Ramos sugiere Juan Candela fue probablemente uno de los primeros batá en Miami con Mario Arango y Onelio Scull ser el primero en llevar batá consagrada de Cuba a los Estados Unidos.

|

|

Second Wave: Musical Marielitos

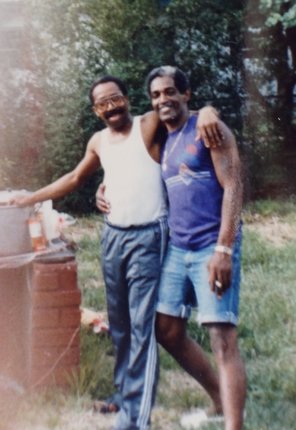

The explosion of Santería in the United States and specifically Miami happened, however, following the mass migration of around a hundred and twenty-five thousand Cubans who arrived in Southern Florida during the period known as the 1980 Mariel Boatlift. Not only did this mass exodus bring thousands of Regla de Ocha devotees to the United States, it brought key musicians whose knowledge of rhythms, songs, rituals and drum making was unprecedented in the United States. Among those Cuban exiles who either lived or spent a significant amount of time performing in Miami were: Orlando ‘Puntilla’ Rios, Juan ‘El Negro’ Raymat, Ezequiel Torres, Lacho Rivero, Osvaldo Millet, Luisito Oferere, Jorge Iturralde, El Surdo, El Palle, Felito Oveido, Julito Balsinde, Angel Miyares, ‘Rumberito’, Pedro ‘El Asmático’ Orta and Lorenzo Peñalver to name a few. Two of these men, Orlando ‘Puntilla’ Rios and Juan ‘El Negro’ Raymat, stand out for their pioneering influence on ritual musical tradition in the United States during the 80s and 90s. Travelling frequently between New York and Miami, as well as other parts of the United States and Latin America, their impact on the fledgling religious community was immense in terms of the new knowledge they brought from Cuba. The combined song, drumming and drum making expertise of these two men as well as their savvy approach to business changed the oricha musical ritual landscape in the United Sates where they collectively maintained a virtual monopoly over its dissemination for over a decade. [6] Both men had the charisma and ability to provide a quality service for an expanding market and access to a crucial commodity of their trade, fundamento drums. Soon after arriving Raymat sent a family member to collect his set of consecrated drums from Cuba. Soon after Raymat’s drums arrived in the United States, Rios borrowed them and ‘birthed’ a set for himself in Puerto Rico apparently without Raymat’s knowledge. Both men set about training an army of Cuban, Puerto Rican and North American men to play, maintain the drums and adhere to a long list of strict protocols and taboos associated with these ritual instruments. Many of these apprentices went on to become initiated omo Añá, meaning they pledged an oath to the deity Añá and became part of an exclusive heterosexual male-only brotherhood, giving them access to playing, making and owning fundamento batá with several of them dedicating a large part of their lives to the tradition and to passing it on to the next generation. Although some Cubans arrived knowing how to play several learnt once they had arrived in the United States, such as Angel Miyares and Arelan Torres. Numerous North American-born men also became renowned tamboreros (batá players) and/or drum owners; El Denny and Skip Burney for example who are featured in this project. Angel, El Denny and Skip all began their apprenticeships in the 1980s and are still playing regularly in Miami over thirty years later. Most of these musicians featured in this project have been part of the ritual music scene since the 80s, a period many referred to as its heyday. At this time those musicians who knew how to play were in high demand, playing several tambores a week, sometimes even two a day. They claim this was a time when those involved took pride in the ritual and musical protocols of the tradition – something they believe is now becoming lost.

|

Segunda Ola: Marielitos Musicales

No sólo este éxodo masivo llevo a miles de devotos Regla de Ocha a los Estados Unidos, pero tambien trajo músicos clave cuyo conocimiento de ritmos, canciones, rituales y la toma de tambor no tenian precedentes en los Estados Unidos. Entre los exiliados cubanos que han vivido o pasado una cantidad significativa de tiempo a realizar en Miami fueron: Orlando 'Puntilla' Ríos, Juan 'El Negro' Raymat, Ezequiel Torres , Lacho Rivero, Osvaldo mijo , Luisito Oferere, Jorge Iturralde , El Surdo, El Palle, Felito Oveido , Julito Balsinde, Angel Miyares , 'Rumberito', Pedro 'El asmático' Orta y Lorenzo Peñalver para nombrar unos pocos. Orlando Ríos 'puntilla' y Juan 'El Negro' Raymat cica 1980 (Foto cortesía de El Negro) Dos de estos hombres, Orlando 'Puntilla' Ríos y Juan 'El Negro' Raymat, destacan por su influencia pionera en la tradición musical ritual en los Estados Unidos durante los años 80 y 90. Viajar con frecuencia entre Nueva York y Miami, así como otras partes de los Estados Unidos y América Latina, su impacto en la comunidad religiosa incipiente era inmensa en términos de los nuevos conocimientos que trajeron de Cuba. La experiencia de canción, tambores y la toma de tambor combinado de estos dos hombres, así como se enfoca inteligentemente para los negocios cambian el paisaje ritual oricha musical En los Estados Unidos, donde se mantienen colectivamente un monopolio virtual sobre su difusión durante más de una década. [6] Ambos hombres tenían el carisma y la capacidad de proporcionar un servicio de calidad para un mercado en expansión y el acceso a un bien fundamental de su comercio, tambores fundamentos. Un poco después de llegar, Raymat envió un miembro de la familia a recoger su juego de tambores consagrados de Cuba. Poco después de la batería de Raymat llegaron a los Estados Unidos, Ríos ellos prestaron y 'dio a luz' un conjunto por sí mismo en Puerto Rico, aparentemente sin el conocimiento de Raymat. Ambos hombres se dedicaron a la formación de un ejército de Cuba, Puerto Rico y los hombres de América del Norte para tocar, mantener los tambores y se adhieren a una larga lista de protocolos estrictos y tabúes asociados con estos instrumentos rituales. Muchos de estos aprendices pasaron a convertirse iniciada como La explosión de la Santería en los Estados Unidos y, específicamente, Miami pasó, sin embargo, a raíz de la migración masiva de alrededor de ciento veinticinco mil cubanos que llegaron en el sur de la Florida durante el período conocido como el 1980 Mariel. Ana, lo que significa que se comprometieron un juramento a la deidad Ana y pasaron a formar parte de una hermandad sólo para hombres heterosexuales exclusiva, que les da acceso a jugar, hacer y ser dueño de fundamento batá con varios de ellos dedicar una gran parte de su vida a la tradición y para pasarlo a la siguiente generación. Aunque algunos cubanos llegaron saber cómo jugar varios aprendido una vez que habían llegado a los Estados Unidos, tales como Angel Miyares y Arelan Torres. Numerosos hombres nacidos en América del Norte también se hicieron famosos tamboreros (jugadores batá) y / o propietarios de tambor; El Denny y Skip Burney, por ejemplo, que se muestran en este proyecto. Ángel, El Denny y Skip todos comenzaron su aprendizaje en la década de 1980 y todavía están jugando regularmente en Miami hace más de treinta años más tarde. La mayoría de estos músicos destacados en este proyecto han sido parte de la escena de la música ritual desde los años 80, un período de muchos referido como su apogeo. En este momento los músicos que sabían cómo jugar tenían una gran demanda, jugando varios tambores a la semana, a veces incluso dos al día. Afirman que esto era un momento en que los implicados se enorgullecían de los protocolos rituales y musicales de la tradición - algo que ellos creen ahora se está perdido. Vertical Divider

|

|

Only initiated drummers are allowed to sit and eat at the mesa de Añá, a ritual meal that takes place before a tambor. In this video Kenneth ‘Skip’ ‘Brinquito’ Burney is leading the chant. At the end of the meal, the drummers place a ‘derecho’ (ritual payment) in the bowl for the apetebi, a daughter of Ochun, who serves them. Although this ceremony was brought to the United States from Cuba, it is now more common outside of the island (Filmed by Vicky Jassey, 2nd April 2017)

|

Sólo tambores iniciados se les permite sentarse y comer en la mesa de Ana, una comida ritual que tiene lugar antes de que un tambor. En este video Kenneth 'Skip' 'Brinquito' Burney está llevando el canto. Al final de la comida, las baterías colocan un (pago ritual) 'derecho' en el recipiente para la Apetebi, una hija de Ochún, que les sirve. Aunque esta ceremonia fue llevada a los Estados Unidos desde Cuba, que ahora se encuentra fuera más común de la isla (Filmado por Vicky Jassey 2 de abril 2017)

Vertical Divider

|

|

Third Wave: New styles and a 'flooded market'.

The mid-90s saw another surge of Cubans emigrating to the United States following increased economic hardship as a result of the withdrawal of the Soviet Union from Cuban affairs. For example, in 1993 there were under 3,000 immigrants but by 1994 this number had jumped to 38,000 following regime and visa regulation changes between the two countries – numbers have since continued to rise. [9] Among them, throngs of musicians settled in Miami wanting to continue or in some cases begin their career in ritual music. The arrival of this new generation, however, has caused some controversy among the second wave of musicians working in Miami since the 80s. The market, they complain, has become flooded, making it much harder to get regular work and forcing many professional ritual musicians to look for other sources of income. Many of the drummers I spoke with suggested that there may now be more than fifty sets of Añá in Miami compared to only two or three in the 80s. Also, the newcomers arrived with a new faster and less constrained style of playing batá. This modern approach frees up the drummer to embellish and improvise to a much greater degree, something the older generation considers a move away from its heritage, a move they fear will lead to the loss of a time-honoured tradition. A similar sentiment was expressed by several older figureheads I spoke with during my 2015 field research such as Angel Bolaños, Octavio Rodriguez, Irian Lopez and Javier Campos. Voices representing the third wave of musicians from around 1995 until the present are largely missing from this project as it has concentrated mainly on the second wave, many of whom have passed away while others are now in their 70s and 80s. However, the oral histories of Philbert Armenteros, who arrived in 1995 and Arelan Torres, who arrived in 2000 play some part in representing this generation. Needless to say, the tradition continues to thrive in Miami and the United States as a whole, albeit in a different way to how it was pre- and post-Mariel boatlift. We hope that documentation of the current oricha musical community in Southern Florida will take place in the not too distant future by others passionate about preserving its history. |

Vertical Divider

Tercera Ola: Los nuevos estilos y un 'mercado inundado'

A mediados de los años 90 vieron otra oleada de cubanos emigrar a los Estados Unidos tras el aumento de las dificultades económicas como consecuencia de la retirada de la Unión Soviética de los asuntos cubanos. Por ejemplo, en 1993 había menos de 3.000 inmigrantes, pero en 1994 este número había aumentado a 38.000 después de los cambios de régimen y regulación de visados entre los dos países - los números desde entonces han seguido aumentando. [9] Entre ellos, una multitud de músicos establecieron en Miami querer continuar o en algunos casos comenzar su carrera en la música ritual. La llegada de esta nueva generación, sin embargo, ha causado cierta controversia entre la segunda ola de músicos que trabajan en Miami desde los años 80. El mercado, se quejan, se ha convertido inundado, lo que es mucho más difícil conseguir un trabajo regular y obligando a muchos músicos profesionales rituales que buscar otras fuentes de ingresos. Muchos de los músicos con los que hablé sugirió que puede haber ahora más de cincuenta conjuntos de Ana, en Miami en comparación con sólo dos o tres de los 80. Además, los recién llegados llegaron con un nuevo estilo más rápido y menos restringida de jugar Bata. Este enfoque moderno libera el batería para embellecer e improvisar en un grado mucho mayor, algo que la generación de más edad considera un alejamiento de su patrimonio, un movimiento que temen que dará lugar a la pérdida de una larga tradición. Un sentimiento similar fue expresada por varios mascarones de proa de mayor edad los que hablé durante mi investigación de campo 2015 como Angel Bolaños, Octavio Rodriguez, Irian Lopez y Javier Campos. Voces que representan la tercera ola de músicos desde alrededor de 1995 hasta la actualidad están en gran medida ausentes de este proyecto, ya que se ha concentrado principalmente en la segunda ola, muchos de los cuales han fallecido, mientras que otros se encuentran ahora en sus 70s y 80s. Sin embargo, las historias orales de Philbert Armenteros, que llegó en 1995 y Arelan Torres, que llegaron en 2000 juegan algún papel en la representación de esta generación. Ni que decir tiene, la tradición continúa prosperando en Miami y Estados Unidos en su conjunto, aunque de una manera diferente a como era antes y después de la boatlift Mariel. Esperamos que la documentación de la comunidad oricha musical actual en el sur de la Florida se llevará a cabo en un futuro no muy lejano por otros apasionados por la preservación de su historia. |

|

Dr Miguel ‘Willie’ Ramos discusses some of the changes he has experienced in ritual musical ceremonial protocols and the influences he believes are the source of these changes. Interview by Vicky Jassey with David Pattman, Miami: 9th March 2017.

|

Vertical Divider

Dr. Miguel 'Willie' Ramos analiza algunos de los cambios que ha experimentado en los protocolos ceremoniales rituales musicales y las influencias que cree que son la fuente de estos cambios.de marzo de 2017.

|

|

Footnotes

[1] In the contexts of this project ‘ritual oricha music’ refers to batá and güiro. This site assumes the reader has some basic knowledge about Regla de Ocha and its music. For more detailed information on oricha music see suggested reading list below. [2] Fernando Ortiz and Norma Suárez Suárez, Los tambores batá de los yorubas (Publicigraf, 1994:158); Miguel Ramos, ‘The Empire Beats On: Oyo, Bata Drums, and Hegemony in Nineteenth Centuary Cuba’ (Ph.D. dissertaion, Florida International University, 2000:177-178); Katherine Dunham and VèVè A Clark, Kaiso!: Writings by and about Katherine Dunham (Madison, Wis.: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 2006:483/604). [3] Capone Stefania. Des batá à New York: le rôle joué par la musique dans la diffusion de la santería aux États-Unis (2006:28) [Online]. Available at: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/oaiart?codigo=2224342. |

Vertical Divider

[4] John Amira, ‘Añátivity: A Personal Account of the Early Batá Community in New York City’, in The Yoruba God of Drumming: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Wood That Talks, ed. Amanda Villepastour (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2016:220).

[5] Ramos (2000:179) [6] Capone (2006:27) [7] Rosenblum, M.R. and Hipsman, F. (2015) Normalization of Relations with Cuba May Portend Changes to U.S. Immigration Policy [online]. Available at: http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/normalization-relations-cuba-may-portend-changes-us-immigration-policy [Accessed 13th March, 2017]. |

Further Reading

Altman, Thomas. 1999. Cantos Lucumi a los orichas. Hamburg: Oche.

Amira, John and Steven Cornelius. 1992. The Music of Santería: Traditional Rhythms of the Batá Drums. Crown Point, IN: White Cliffs Media.

Brown, David H. 2003. Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cabrera, Lydia. 1954. El Monte. Havana: Ediciones C.R.

––––––. 1980 [1974] Yemayá y Ochún: Kariocha, Iyalorichas y Olorichas. New York: Colección de Chicherukú en el exilio.

Cornelius, Steven. 1989. The Convergence of Power an Investigation into the Music Liturgy of Santeria in New York City. Los Angeles: University of California.

––––––.1995. ‘Personalizing Public Symbols Through Music Ritual: Santeria's Presentation to Alia’. In Latin American Music Review, 16(1): 42-57.

Delgado, Kevin Miguel. 1997. Negotiating the Demands of Culture: Bata Drumming in San Diego. Masters dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Friedman, Robert. 1982. Making an Abstract World Concrete: Knowledge, Competence and Structural Dimensions of Performance among Batá; Drummers in Santería. Ph.D dissertation, Indiana University.

Hagedorn, Katherine J. 2001. Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santeria. Washington: Smithsonian Books.

Marcuzzi, Michael David. 2005. A Historical Study of the Ascendant Role of Bàtá Drumming in Cuban Òrìṣà Worship. Ph.D. dissertaion, York University, Toronto.

Mason, Michael Atwood. 1994. ‘"I Bow My Head to the Ground": The Creation of Bodily Experience in Cuban-American Santeria Initiation’. Journal of

American Folklore 107 No. 423 Bodylore, 23-39.

Olsen, Dale, and Daniel Sheehy. 2007 The Garland Handbook of Latin American Music. Routledge.

Schweitzer, Kenneth. 2013. The Artistry of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming: Aesthetics, Transmission, Bonding, and Creativity. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Sublette, Ned. 2007. Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo. Chicago, Ill: Chicago Review Press.

Vaughan, Umi and Carlos Aldama. 2012. Carlos Aldama’s Life in Batá: Cuba, Diaspora, and the Drum. Bloomington, Indian: Indiana University Press.

Vélez, María Teresa. 2000. Drumming for the Gods. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Villepastour, Amanda. 2015. The Yoruba God of Drumming: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Wood That Talks. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Vincent [Villepastour], Amanda. 2006. ‘Batá Conversations: Guardianship and Entitlement Narratives about the Bata in Nigeria and Cuba’. PhD, School of Oriental & African Studies.

Altman, Thomas. 1999. Cantos Lucumi a los orichas. Hamburg: Oche.

Amira, John and Steven Cornelius. 1992. The Music of Santería: Traditional Rhythms of the Batá Drums. Crown Point, IN: White Cliffs Media.

Brown, David H. 2003. Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cabrera, Lydia. 1954. El Monte. Havana: Ediciones C.R.

––––––. 1980 [1974] Yemayá y Ochún: Kariocha, Iyalorichas y Olorichas. New York: Colección de Chicherukú en el exilio.

Cornelius, Steven. 1989. The Convergence of Power an Investigation into the Music Liturgy of Santeria in New York City. Los Angeles: University of California.

––––––.1995. ‘Personalizing Public Symbols Through Music Ritual: Santeria's Presentation to Alia’. In Latin American Music Review, 16(1): 42-57.

Delgado, Kevin Miguel. 1997. Negotiating the Demands of Culture: Bata Drumming in San Diego. Masters dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles.

Friedman, Robert. 1982. Making an Abstract World Concrete: Knowledge, Competence and Structural Dimensions of Performance among Batá; Drummers in Santería. Ph.D dissertation, Indiana University.

Hagedorn, Katherine J. 2001. Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santeria. Washington: Smithsonian Books.

Marcuzzi, Michael David. 2005. A Historical Study of the Ascendant Role of Bàtá Drumming in Cuban Òrìṣà Worship. Ph.D. dissertaion, York University, Toronto.

Mason, Michael Atwood. 1994. ‘"I Bow My Head to the Ground": The Creation of Bodily Experience in Cuban-American Santeria Initiation’. Journal of

American Folklore 107 No. 423 Bodylore, 23-39.

Olsen, Dale, and Daniel Sheehy. 2007 The Garland Handbook of Latin American Music. Routledge.

Schweitzer, Kenneth. 2013. The Artistry of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming: Aesthetics, Transmission, Bonding, and Creativity. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Sublette, Ned. 2007. Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo. Chicago, Ill: Chicago Review Press.

Vaughan, Umi and Carlos Aldama. 2012. Carlos Aldama’s Life in Batá: Cuba, Diaspora, and the Drum. Bloomington, Indian: Indiana University Press.

Vélez, María Teresa. 2000. Drumming for the Gods. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Villepastour, Amanda. 2015. The Yoruba God of Drumming: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Wood That Talks. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Vincent [Villepastour], Amanda. 2006. ‘Batá Conversations: Guardianship and Entitlement Narratives about the Bata in Nigeria and Cuba’. PhD, School of Oriental & African Studies.